I’ve spoken more than once in this forum about Uva Hester, a pioneering Extension public health educator of the early 20th century.

I’ve spoken more than once in this forum about Uva Hester, a pioneering Extension public health educator of the early 20th century.

Writing her weekly report in June 1920, Hester, a Tuskegee Institute health educator, related a horrifying experience with one of her clients, a young woman and tuberculosis patient, bedridden for more than a year, suffering from openings in her chest and side as well as a bedsore the size of a human hand on her back.

Her family had made no provision to protect her from the flies that swarmed around her, Hester soberly related.

It was a sight that almost defies human comprehension in the 21st century but that was all too common among southerners, particularly black southerners, in early 20th century Alabama.

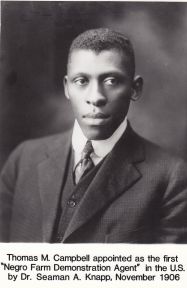

Hester, along with a team of poorly funded but determined Tuskegee Institute educators, led by an equally determined and resourceful agent named Thomas Campbell, vowed to do something about it. Working with the state’s health department, Tuskegee educators fanned out across the state, not only to care for the chronically ill but also to show their families and neighbors what they could do to prevent the spread of tuberculosis and other unsafe, if not potentially deadly, conditions.

I was reminded of Hester today after reading a New York Times article attesting to the immense advances in human health and well-being that have occurred within the last few centuries.

The Times reports that for almost three decades, a team of researchers led by Nobel Laureate Robert W. Fogel has been diligently investigating how changes in the size and shape of the human body reflect the dramatic strides in food production and human health and nutrition. The results of this study have been compiled into a book titled “The Changing Human Body: Health, Nutrition and Human Development in the Western World Since 1700,” which will be published by Cambridge University Press in May, 2011.

The researchers maintain that “in most if not quite all parts of the world, the size, shape and longevity of the human body have changed more substantially, and much more rapidly, during the past three centuries than over many previous millennia” — as they stress, “minutely short by the standards of Darwinian evolution.”

One of the nation’s leading demographers and sociologists, the University of Pennsylvania’s Samuel Preston, puts the issue into sharp perspective: Without the advances in nutrition, sanitation, and medicine, only half of the current American population would be alive today.

The last 100 years of progress are due in no small measure to Uva Hester and the thousands of Extension public health educators who have acquainted Americans with working knowledge that has not only improved their lives but, in an immense number of cases, actually saved them.

The Tuskegee Institute Extension efforts are only one of many examples of Extension-sponsored efforts aimed at improving basic nutritional and health skills, especially among limited resource families. For example, in the early 1960s, five rural Alabama counties served as pilot sites for what later became known as the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP), which was developed to provide directed education to limited resource families to improve their eating habits and homemaking skills. The program was eventually expanded to all 50 states.

The role that pioneering Extension nutritional and health educators have played in these advances, while impressive, should not detract from the equally critical contributions of Extension agricultural educators in helping the nation’s farmers secure one of the greatest technological achievements in human history: a comparatively cheap, diverse and abundant food supply.

As Fogel stresses, technological advances rescued farmers from the endless cycle of subsistence farming. For example, colonial-era farmers worked some 78 hours during a five-and-a-half day week. Farmers needed more food to grow and gain strength, but they were unable to grow more food without being stronger.

The improved yields secured by advanced scientific farming methods broke this cycle and changed the face of farming forever.

The strong Extension emphasis on adopting farm mechanization — replacing draft animals with farm machinery — ultimately helped free up millions of acres of agricultural land to supply human needs — land that had been previously tied up to feed farm animals.

Despite these immense strides, Extension educators still face a bevy of challenges.

Fogel concedes that when he first began his research, he never imagined that technological advances would lead to chronic problems of overnutrition, which have contributed to obesity and related chronic conditions such as heart disease, stroke, hypertension and certain types of cancer.

Extension nutrition and health educators increasingly are being called upon to demonstrate practical ways to avoid these conditions.

Meanwhile, Extension agricultural educators are gearing up to help farmers build a new farming model by mid-20th century that not only incorporates both scientific farming advances and sustainable practices but that is also equipped to feed some 9 billion people across the planet using less land, less water and less energy.